Blog Post

Gerrymander Gazette: I’ll See You in Court Edition

August 29, 2019

In the July 2, 2019 edition of the Gerrymander Gazette, we discussed the next phase of the fight to end gerrymandering. This month, we will take a closer look at one of the fronts in that fight: state court lawsuits.

“Free Elections” and Other State Constitutional Clauses

On June 27, 2019, the U.S. Supreme Court dealt a blow to democracy in its ruling in Rucho v. Common Cause and Lamone v. Benisek. The Court stated in a 5-4 opinion that partisan gerrymandering is a nonjusticiable political question that federal courts will not police. Despite this setback, Chief Justice Roberts identified approaches that can serve as an alternative to federal court intervention. He cited state reforms like independent citizen redistricting commissions and others that can be passed by ballot initiative. In addition, the majority states that “(p)rovisions in state statutes and state constitutions can provide standards and guidance for state courts to apply.” Challenging maps as partisan gerrymanders under state law in state court is a tactic that already succeeded in Pennsylvania and that is currently being deployed in North Carolina in the first post-Rucho/Lamone case to challenge a partisan gerrymander. State constitutional provisions that are not found in the U.S. Constitution and the ability of state courts to have the final say in interpreting state constitutions provide voting rights advocates with the next frontier in the fight for fair representation.

State supreme court interpretations of state law are generally not reviewable by the U.S. Supreme Court. As a result, the U.S. Supreme Court’s ruling in Rucho and Lamone has no impact on the ability of state courts to interpret their state constitutions in more strongly pro-voter ways than the U.S. Supreme Court has interpreted the U.S. Constitution. State court strategies that are potentially useful to partisan gerrymandering plaintiffs include advocating for pro-voter interpretations of state constitutional provisions that are similar to federal provisions and litigating state constitutional provisions that have no federal analogues.

State constitutions typically contain provisions guaranteeing the right to free speech, free association, and equal protection that have clearly analogous provisions in federal law like the First and Fourteenth Amendments. However, state supreme courts have the authority to interpret even identical provisions of state constitutions differently than those provisions’ U.S. Constitution counterparts. In some states, judicial precedent has supported a “lockstep” approach to interpretation in which state courts have adopted federal court interpretations of similar constitutional clauses. However, a state supreme court may reject its own precedent and move to a more independent interpretation of a state constitutional clause.

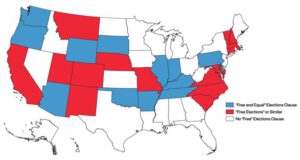

State constitutions may also contain provisions related to elections that do not have analogous counterparts in the U.S. Constitution. State supreme courts may interpret these provisions in ways that provide protections for voters that are stronger than federal law. For example, 28 states have clauses guaranteeing “free” elections and 13 of those 28 guarantee the right to “free and equal elections.” Due to their more specific application to voting rights, these clauses may provide the legal framework advocates need to launch state court litigation challenging voting districts that have been manipulated for partisan purposes.

Success in Pennsylvania

In 2017, the Public Interest Law Center filed a lawsuit on behalf of individual voters and the League of Women Voters of Pennsylvania in Pennsylvania Commonwealth Court to challenge Pennsylvania’s congressional districts. In the redistricting cycle following the 2010 census, Pennsylvania was widely identified as one of the worst gerrymanders in the country. Despite a typically even vote split between Democrats and Republicans in every election since the post-census approval of new districts in 2011, Republicans won 13 of 18 seats each time. The plaintiffs argued that the districts constituted a partisan gerrymander that violated several provisions of the Pennsylvania Constitution, including the “free and equal elections” clause. Common Cause filed an amicus brief in the case detailing the long history of the clause in Pennsylvania.

The Pennsylvania Supreme Court struck down the congressional map, stating that the court’s own precedent had “established that any legislative scheme which has the effect of impermissibly diluting the potency of an individual’s vote for candidates for elective office relative to that of other voters will violate the guarantee of ‘free and equal’ elections afforded by Article I, Section 5.” The court relied solely on the Free and Equal Elections Clause and declined to decide whether the map also violated other provisions of the Pennsylvania Constitution that the plaintiffs raised. The opinion added that the lack of an analogous clause in the U.S. Constitution meant that its precedent interpreting state constitutional provisions in lockstep with the U.S. Supreme Court’s interpretation of analogous federal clauses did not apply.

Success in League of Women Voters of Pennsylvania before the Rucho/Lamone decision turned out to be a harbinger of things to come. It established a new and innovative approach in the fight for fair representation now that the U.S. Supreme Court has shut the door on federal court challenges to partisan gerrymandering. Common Cause is currently awaiting a trial court decision in Common Cause v. Lewis, the first case to test this approach post-Rucho/Lamone.

Common Cause v. Lewis and Another North Carolina Gerrymander

Last year, Common Cause, the North Carolina Democratic Party, and individual North Carolina voters sued legislators in North Carolina state court on the grounds that the General Assembly map is an illegal partisan gerrymander that violates the North Carolina Constitution. Our claim in Common Cause v. Lewis is that the districts violate the rights of the plaintiffs and all Democratic voters in North Carolina under the North Carolina Constitution’s Free Elections, Equal Protection, Freedom of Speech, and Freedom of Assembly clauses.

In 2011, as part of a national movement by the Republican Party to entrench itself in power through redistricting, North Carolina Republicans’ mapmaker manipulated district boundaries with surgical precision to maximize the political advantage of Republican voters and minimize the representational rights of Democratic voters. It worked. In 2012, 2014, and 2016, Republicans won veto-proof super-majorities in both chambers of the General Assembly despite winning only narrow majorities of the overall statewide vote.

In 2017, after federal courts struck down some of the 2011 districts as unconstitutional racial gerrymanders, Republicans redoubled their efforts to gerrymander the district lines on partisan grounds. They instructed the same Republican mapmaker to use partisan data and prior election results in drawing new districts. In both the North Carolina House and North Carolina Senate elections in 2018, Democratic candidates won a majority of the statewide vote, but Republicans still won a substantial majority of seats in each chamber. The maps are impervious to the will of the voters. Because North Carolina is one of the few states in the country where the governor lacks power to veto redistricting legislation, the General Assembly alone will control the next round of redistricting after the 2020 census.

Accordingly, as things currently stand, the Republican majorities in the General Assembly elected under the existing maps will have free reign to redraw both state legislative and congressional district lines for the next decade. This perpetuates a vicious cycle in which representatives elected under one gerrymander enact new gerrymanders both to maintain their control of the state legislature and to rig congressional elections for ten more years. Only the intervention of the judiciary can break this cycle and protect the constitutional rights of millions of North Carolinians.

The plaintiffs are asking the court to rule that the North Carolina Constitution prohibits partisan gerrymandering, to throw out the gerrymandered 2017 plans and to appoint a referee (also known as a special master) to create new, constitutional legislative districts for the 2020 primary and general elections. The new districts must be drawn without any partisan political consideration. Regardless of the outcome at trial, an appeal that ends with a decision from the North Carolina Supreme Court is likely. Our hope is that the North Carolina Supreme Court will interpret both the state’s Free Elections Clause and its provisions that are analogous to federal law in ways that prohibit partisan manipulation of voter districts. Common Cause v. Lewis represents an important test case to determine whether state courts will become a much needed venue for protecting voters’ fundamental democratic rights.

This newsletter has been produced by Common Cause and compiled by Dan Vicuna. Subscribe to the Gerrymander Gazette here. For more information or to pass along news, contact Dan Vicuna.