Blog Post

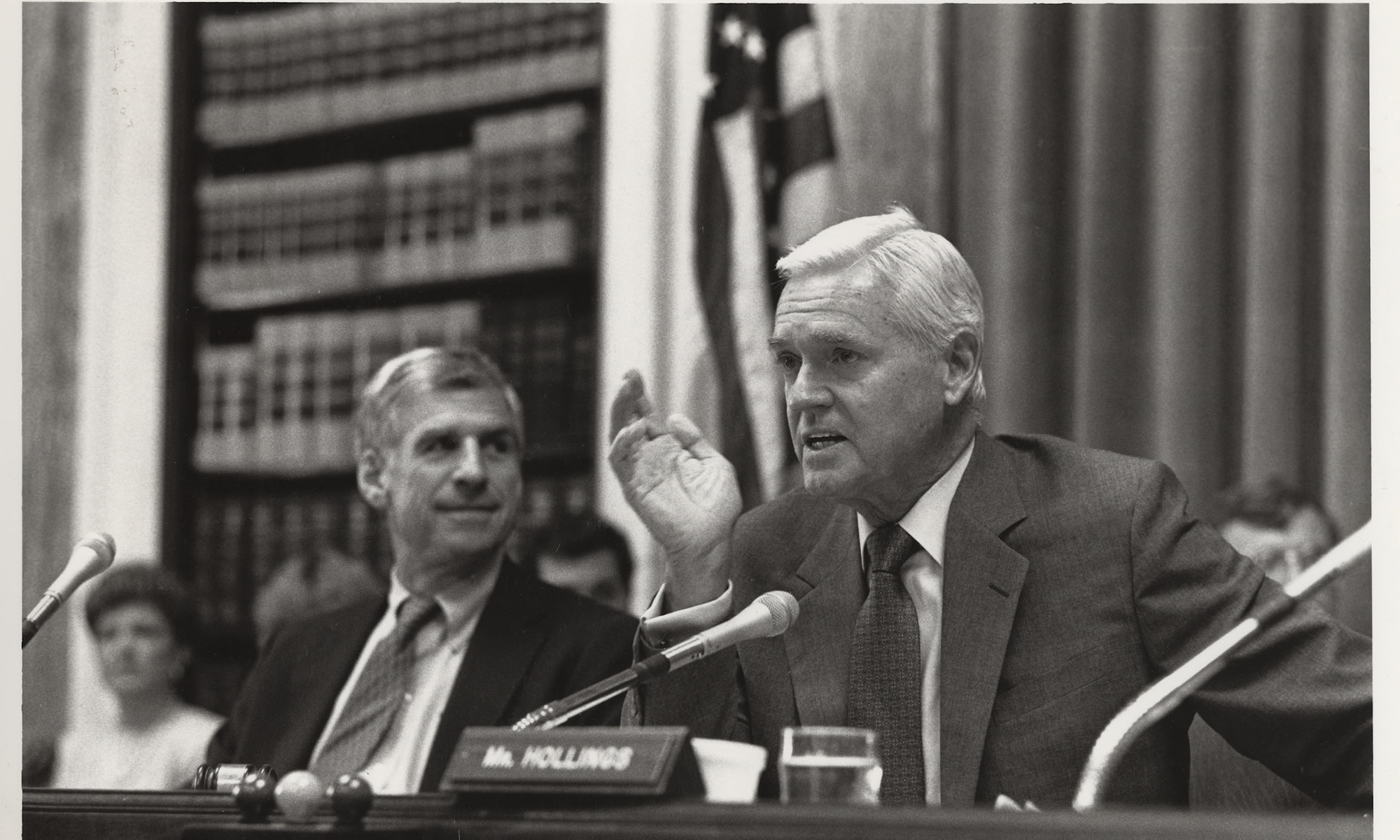

Fritz Hollings: An Appreciation

Readers of this space may recall that I worked for many years (15) for U.S. Senator Fritz Hollings (D-SC) when I first came to Washington, way back in 1970. Fritz passed away on April 6 at age 97. He was a formative influence on my life and career throughout the almost 50 years I knew him. For me, he was also a model of what a public servant should be. He was proud of public service, believed in the public interest, achieved much, and had a feel for policy and politics the likes of which I have never since encountered. That “feel” was in his brain and in his gut.

Hollings was born January 1, 1922, in his beloved Charleston. He won admission to The Citadel at age 16, graduated in 1942, and went straight into World War II, serving with the 36th Division and seeing action in North Africa and Europe, winning a Bronze Star and seven combat stars along the way to Allied victory. Returning home, he earned a law degree in two years and was soon asked to run for public office. Elected to the South Carolina House at age 26, he quickly became Speaker Pro Tempore, and then was elected Lt. Governor. By age 37, he was the state’s governor. He traveled the nation in search of new businesses, resulting in over half a million dollars a day committed to industrial investment through the course of his gubernatorial term. His technical education program did pioneering work and was a model for other states. Educational Television (SCETV), teacher pay raises of 38% over his term-limited four years, and a Triple “A” credit rating for the state were other highlights of his governorship. So was ensuring the peaceful integration of Harvey Gantt into Clemson University, with Hollings telling the state it had run out of courts and it was time to prove we were a government of laws and not of men. On the wrong side of Brown v. Board of Education, he nevertheless had already attempted to pass an anti-lynching bill as early as 1949. As current U.S. House of Representative Majority Whip James Clyburn (D-SC) noted at Hollings’ funeral last month, Fritz had an amazing capacity for growth, and he grew to be a leader in equal opportunity and civil rights. He was, in fact, the only southern senator to oppose all weakening amendments to the renewal of the Civil Rights Act in 1982. In a history-making gesture in 2015, Hollings asked that his name be removed from the federal courthouse in Charleston and proposed that it be named instead for former Federal Judge J. Waties Waring, a pioneering civil rights jurist of the 1940s whose decisions were influential in paving the way for Brown v. Board of Education. At Hollings’ behest, legislation was passed and the building’s name was changed. For a sitting or retired senator to urge that his name be removed from a federal building was, to the best of my knowledge, a first in U.S. history.

Hollings was born January 1, 1922, in his beloved Charleston. He won admission to The Citadel at age 16, graduated in 1942, and went straight into World War II, serving with the 36th Division and seeing action in North Africa and Europe, winning a Bronze Star and seven combat stars along the way to Allied victory. Returning home, he earned a law degree in two years and was soon asked to run for public office. Elected to the South Carolina House at age 26, he quickly became Speaker Pro Tempore, and then was elected Lt. Governor. By age 37, he was the state’s governor. He traveled the nation in search of new businesses, resulting in over half a million dollars a day committed to industrial investment through the course of his gubernatorial term. His technical education program did pioneering work and was a model for other states. Educational Television (SCETV), teacher pay raises of 38% over his term-limited four years, and a Triple “A” credit rating for the state were other highlights of his governorship. So was ensuring the peaceful integration of Harvey Gantt into Clemson University, with Hollings telling the state it had run out of courts and it was time to prove we were a government of laws and not of men. On the wrong side of Brown v. Board of Education, he nevertheless had already attempted to pass an anti-lynching bill as early as 1949. As current U.S. House of Representative Majority Whip James Clyburn (D-SC) noted at Hollings’ funeral last month, Fritz had an amazing capacity for growth, and he grew to be a leader in equal opportunity and civil rights. He was, in fact, the only southern senator to oppose all weakening amendments to the renewal of the Civil Rights Act in 1982. In a history-making gesture in 2015, Hollings asked that his name be removed from the federal courthouse in Charleston and proposed that it be named instead for former Federal Judge J. Waties Waring, a pioneering civil rights jurist of the 1940s whose decisions were influential in paving the way for Brown v. Board of Education. At Hollings’ behest, legislation was passed and the building’s name was changed. For a sitting or retired senator to urge that his name be removed from a federal building was, to the best of my knowledge, a first in U.S. history.

Hollings was one of the earliest leaders in supporting John F. Kennedy’s campaign for the Presidency in 1960. He remembered this time as one of the most exciting of his career in politics, and he always valued his friendship with Jack and his brothers. (That didn’t mean, of course, that they always agreed.) In 1962 Fritz suffered his only electoral defeat at the hands of powerful incumbent U.S. Senator Olin D. Johnston (D-SC). Gracious in defeat, he won the special election to the Senate when Johnston died in 1966. Hollings was elected to the Senate seven times and became the eighth longest-serving senator in our history, retiring in 2005.

Hollings was known for his quick wit and witticisms. “When in danger, when in doubt, run in circles scream and shout,” he said about certain politicians. “The ox is in the ditch,” he would say when a serious problem confronted the nation. “There’s no education in the second kick of a mule.” “A man convinced against his will is a man of the same opinion still.” “On the way through life make this your goal—keep your eye on the doughnut and not the hole.” These were just a few of the memorable sayings that could fill a book. Once in a while, a particularly pungent utterance would get him into trouble—but Fritz was Fritz and said what he thought.

He was above all a serious man engaged in serious business. He tackled his job with total immersion and uncommon dedication. Before he voted, he dug deep into every issue. I know, because I was there, and his devoted staff dug with him. His expertise on the economy, the budget, international trade, national security, foreign policy, education, energy, telecommunications (of which more anon), oceans and the environment, health and cancer research, and creating an opportunity for all Americans, led to an amazing record of accomplishment. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), Coastal Zone Management, protection of marine mammals and fisheries, the Ocean Dumping Act, funding for cancer research, the Automobile Fuel Economy Act, and toughening port and airport security are but a few of his many legislative contributions. His 1970 book, The Case Against Hunger, was an early and important contribution to the development of nutritional and anti-poverty programs like Women, Infants & Children Feeding. “It’s cheaper to feed the child than to jail the man,” he said, and “The only way we can raise the income level of any is to raise the education of all.” He fought rigorously and to the end to control campaign spending, convinced that the role of big money was corrupting our elections and our democracy. He was a strong proponent of a value-added tax (VAT) and wrote many newsletters on the subject even after he retired. Also in retirement, he raised money for the Hollings Cancer Center at the Medical University of South Carolina.

Fritz believed that political office entailed the responsibility to really learn about issues and to share what he learned with his constituents. To him, politics carried a strong educational component. He was fond of the Irish statesman Edmund Burke’s quote that “Your representative owes you not his industry only, but his judgment, and he betrays instead of serving you if he sacrifices it to your opinion.” Don’t get me wrong—Fritz was mostly in step with South Carolina voters on issues; otherwise, he would not have been reelected so many times. But if he dug deep and came to new knowledge, he shared that knowledge and explained his reasoning. So it was with hunger, civil rights, the Panama Canal treaties (which he changed his mind to support but also greatly strengthened in Congress), and various national security issues wherein he was habitually strong but studiously discerning in which weapons systems to support or deny.

Since many readers of this piece are involved in communications, I add a little on that. Fritz chaired the Senate Commerce Committee for years and was instrumental in carving telecommunications and media policies. The critically-important Telecommunications Act of 1996 didn’t go as far as he would have liked given industry opposition to some of his proposals, but he fought mightily for competition and for making sure the public interest was paramount. (The Act mentions “public interest” over 110 times.) Had this Act been so enforced, rather than subsequently undermined by ridiculous industry litigation and a couple of Federal Communications Commission regimes that went out of their way to allow industry evasion of the rules and regulations established under auspices of the statute, we would not be living in the monopoly-oligopoly world of communications that we inhabit and endure today.

Hollings also believed in participatory politics—not the spectator sport of today but actual civic engagement. Another quote he liked was from long-deceased Elihu Root, who once said that politics is the practical art of self-government and somebody must attend to it if we are to have self-government. The principal ground for reproach against any American citizen, Root concluded, should be that he (or she) is not a politician. Everyone ought to be. That’s a tough challenge these days with politics reduced to a reality show and hyper-partisanship. But the only way to get this ox out of the ditch is for each of us, as citizens, to demand more and organize and vote to make it happen.

Fritz had another blessing beside his brilliance, humor, and commanding personality. She was Peatsy, his wife. We can’t remember him without remembering her. People met Peatsy and people loved her on the spot. She was the best adviser and friend-maker he ever had. Fritz and Peatsy were each bright shining stars in their own right; together they were absolutely dazzling.

I loved the man—the most impressive I ever met. He lives on in me and all those who worked with him with a presence that his passing cannot extinguish. I know I will be seeing him and getting advice and inspiration from him for the rest of my life. It was the country’s good fortune to have such a statesman in its service. It was my good fortune to have such a good and inspiring friend.

Michael Copps served as a commissioner on the Federal Communications Commission from May 2001 to December 2011 and was the FCC’s Acting Chairman from January to June 2009. His years at the Commission have been highlighted by his strong defense of “the public interest”; outreach to what he calls “non-traditional stakeholders” in the decisions of the FCC, particularly minorities, Native Americans and the various disabilities communities; and actions to stem the tide of what he regards as excessive consolidation in the nation’s media and telecommunications industries. In 2012, former Commissioner Copps joined Common Cause to lead its Media and Democracy Reform Initiative. Common Cause is a nonpartisan, nonprofit advocacy organization founded in 1970 by John Gardner as a vehicle for citizens to make their voices heard in the political process and to hold their elected leaders accountable to the public interest.

Originally published by the Benton Foundation.