Article de blog

Quand les nouvelles ne sont pas les nouvelles

I’ve been a news junkie since I was a kid. I still remember lying in bed listening to early returns coming in from the Truman-Dewey Presidential contest of 1948—I say “early returns” because my parents made me turn off the radio hours before Harry snatched victory from the predicted jaws of defeat. My addiction to news continues today and will probably still afflict me when senility arrives, which some may argue has happened already. I eagerly open the door every morning to retrieve my hold-in-the-hand newspapers; throughout the day I check online news sites; I watch the network and local evening news; and late into the evening I surf through the cable channels from Fox to MSNBC to see how the daily shout-downs rage and roar. (The latter is done over my beloved spouse’s objection and occasional ire. Pray for her.)

With all this focus, I should have a nutritious news diet, right? I should feel like a really informed citizen. The problem is: I don’t. I feel less informed as the years go by and less confident about my ability to intelligently exercise my responsibilities as a citizen. Our news diet is low on the nutrients that real democracy depends upon to sustain itself. Our democracy is starving. And there is no such thing as “democracy-lite” that can sustain it over any meaningful stretch of time.

We have never had a golden age of news. I get that. We have endured partisan rags since the days of the Founders. The papers they read were replete with scandal and vehemence that would make most of us blush today. Thomas Jefferson’s supporters characterized John Adams, who we remember as an altogether prim Founding Father, as a “hideous hermaphroditical character”. On the opposing side, Jefferson’s relationship with Sally Hemings was touted far and wide by the Federalist press. And so it went through the years, with many newspapers becoming little more than broadsides leading up to the Civil War and, later, to the yellow journalism behind the Spanish-American War, the Red Scare, and right up to the epidemic of mis- and dis-information that pollutes our public dialogue in this third decade of the twenty-first century.

So, no, I am not advocating a return to some glorious golden era of news and information, although a strong argument can be made that citizens in earlier stages of our nation’s development, even though lacking the technologies for the distribution of news that we presently possess, were sometimes better informed on the issues of their day than we are of ours.

What I am advocating is making our news and information ecosystem better than it is. Much better. We have the tools and resources to do that. What is lacking is the demand and push to get the job done. Yes, we can still find fine investigative reporting from a handful of newspapers, but they reach only a tiny percentage of us. Good journalism is shrinking as the nation’s problems compound. There are now, finally, stirrings of realization that something is amiss in our news world. There is a growing, but still small, realization that the closing of newsrooms, the mass laying off of journalists and newsroom employees, and the shuttering of news bureaus from local communities to state capitals to Washington, DC, to nations overseas, are dangerously diminishing the bank of information that people need to draw on.

At the heart of the problem is the corporatization and financialization of media enterprises that control the news. These include newspapers, broadcasters, cable outlets, and online sites. Many, if not most, independent community news outlets have been bought by huge mega-media companies and hedge funds. These gigantic businesses are out to please Wall Street and the markets. And to pay for their multi-million, and often multi-billion, dollar deals, the first thing they do is cut back on news expenses. Control goes from the local community to the national office C-suite, often many hundreds of miles away from the community supposedly being served. The priority is to pay off the last deal so they can pursue the next one, primarily by selling us, as consumers, to advertisers. We have become products to be sold, not citizens to be informed.

The internet has failed to nourish our news and information diet the way we hoped it would twenty years ago. There are some very fine and valued sites online that practice real journalism, but they are a precious few, not the rule. Original journalism on the big tech platforms is as scarce as wings on a pig. The norm is major platforms poaching the news they distribute directly from newspaper and television newsrooms while failing to make any meaningful investments in journalism despite generating billions of dollars in advertising revenue that traditional media once depended upon. The idea of the internet as the new town square of democracy is a quaint and distant memory.

I certainly don’t deny that there are still papers and stations and online sites that do serve the public interest. They are independent and many times smaller than the giants, and they are dedicated to informing and improving their communities. Most do not survive. Their lot is a hard one and their struggle is steeply uphill, but we salute them for their work. It is not them I’m talking about in this piece.

To cut costs and attract audiences, the big guys replace the expensive journalism that they have cut off at the knees with cheaper, easy-to-produce, glitzy infotainment. The Romans had their bread and circuses to keep the people happy; we have infotainment. Much of what passes for news is murder, mayhem, blood, goofy videos, and endless mind-numbing ads that take up more and more of our viewing time every day. (Don’t we all love those 15-second network news stories that are preceded and followed by multi-minute advertisements?) As for political coverage, much of it has been reduced to ginning up excitement about the latest polls and the electoral horse race. The last few weeks are a clear example. Three years out from the next Presidential contest, the media breathtakingly chart every one-point change in the President’s standing as if that tells us anything important about what we need to know. “Breaking news” the anchors call it. I call it breaking democracy.

“The ox is in the ditch,” my friend Fritz Hollings used to say when a serious problem threw the country off course. How do we get this ox out of the ditch?

Solutions have been suggested. One option is vigorous anti-trust to break up monopolies. The Biden Administration seems significantly more open to this than most of its recent predecessors. (Even many broadcasters have joined the rising chorus to break up the huge technology companies. Of course, they oppose breaking up their own huge conglomerates.) So, there is some promise of action here on the high-tech side, but I believe anti-trust should be an across-media effort. High tech is not our only media problem.

Another option is effective public interest oversight of broadcast and extending it to cable and the high-tech giants. This should be a priority. The Telecommunications Act was written to apply to radio and wire. Don’t all these enterprises fall under that rubric? Aren’t radio and wire what they ride on? Years ago, public interest obligations were taken at least somewhat more seriously, with the expectation that a broadcaster could lose its license if it failed to serve the public interest. Ideally, serving the public interest would mean covering local events like the mayor’s office, the health department, and the schools. And it would also mean representing the diversity of the community, offering opportunity for cultural presentations, and providing forums for balanced public dialogue. Such ideas and proposed guidelines were bitterly opposed by many broadcasters and were never widely implemented. But what a different media environment we would have today had they been required. We desperately need public interest rules and guidelines now. Of course, such requirements would not be identical for each species of media, but crafting sector-appropriate oversight does not entail rocket science. We just need the will to do it. The bottom line is that the airwaves belong to we, the people, not to a handful of conglomerates. The airwaves should be utilized to advance the common good.

These options—anti-trust and public interest oversight—are important initiatives that should be rigorously pursued. They won’t be easily won. Anti-trust cases take years, sometimes decades, to decide, and then come years of appeals and more appeals. Even worse, our current court system has reverted to a horse-and-buggy interpretation of anti-trust that narrows the grounds for findings of harm. Under the current approach, vertical conglomerations that combine both product and distribution are almost always exempted from findings of harm. To me, control over both content and distribution is the very essence of monopoly. If we ever get serious about tackling the many shortcomings of our present judiciary, this must be one of the priorities of reform.

I am more hopeful on the regulatory front, although here, too, it’s an uphill climb. Agencies like the Federal Communications Commission and the Federal Trade Commission were for years under capture by the special interests. Now, under new leadership, both agencies may finally be able to get about the job of protecting the public interest. To make some of the major changes that are needed, legislation may have to be enacted. Unfortunately, the special interests wield unseemly influence in Congress, too. They have even been known to write legislation that is introduced by members. Chalk that up to the power of money. Politique just reported that Apple, Google, and Facebook (Meta) spent more than $55 million lobbying the federal government last year. Add in the largesse that telecoms and traditional media contribute to House and Senate members and we’re talking about some really serious money.

A third option is to get serious about public media. What public media we have now is the jewel of our broadcast system, but it operates on a relative pittance. Other countries spend much more on it than we do. They invest heavily in real news journalism and investigative reporting. They provide facts so people can form their own opinions, rather than spewing opinions without the facts. The United States needs to invest in public media that have the resources to extend their outreach to local communities throughout the country, and to further enhance national and global news and information programming. Some folks worry about government control over public media. But countries abroad have demonstrated that it is relatively simple to build firewalls between public media and the national government. In fact, countries that rank above us on the listing of best democracies are the same ones that have been leading the way in supporting public media. We don’t need to supplant the commercial media we have, but we do need to provide a less self-interested media system than the one that is presently holding America back.

I’m for proceeding on all three fronts: anti-trust, public interest oversight, and public media. Any one of them would be real progress. Two would be better. All three might just deliver the media infrastructure needed to support our always-fragile democracy.

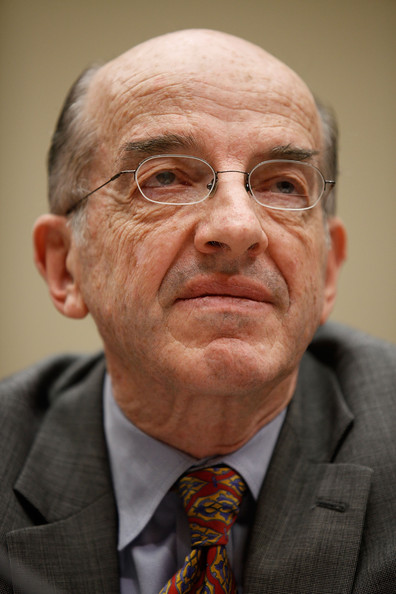

Michael Copps a été commissaire à la Commission fédérale des communications de mai 2001 à décembre 2011 et président par intérim de la FCC de janvier à juin 2009. Ses années à la Commission ont été marquées par sa défense acharnée de « l'intérêt public » ; par sa sensibilisation à ce qu'il appelle les « parties prenantes non traditionnelles » dans les décisions de la FCC, en particulier les minorités, les Amérindiens et les diverses communautés de personnes handicapées ; et par des actions visant à endiguer ce qu'il considère comme une consolidation excessive dans les secteurs des médias et des télécommunications du pays. En 2012, l'ancien commissaire Copps a rejoint Common Cause pour diriger son initiative de réforme des médias et de la démocratie. Common Cause est une organisation de défense des droits non partisane et à but non lucratif fondée en 1970 par John Gardner pour permettre aux citoyens de faire entendre leur voix dans le processus politique et de demander des comptes à leurs dirigeants élus en faveur de l'intérêt public. En savoir plus sur Commissaire Copps à L'agenda de la démocratie médiatique : la stratégie et l'héritage du commissaire de la FCC, Michael J. Copps