Blog Post

Building Democracy 2.0: The Misdirected Attempts at Electoral Reform in the U.S.

Introduction

Now that we have examined the types of electoral systems and seen how they evolved to address specific problems on the ground, we can better understand reform efforts in the U.S. This story picks up during the Progressive Movement, which witnessed a number of reforms in response to the extreme wealth disparities, labor unrest, rural poverty, and urban dislocation at that time. Political dysfunction and bitter polarization crippled government’s ability to respond meaningfully to these crises. In response, “Fighting” Bob LaFollette and other leaders of the Progressive Movement galvanized public support around a series of reforms related to democracy. The secret ballot, direct election of U.S. Senators, suffrage for women and citizen initiative all gained passage. In addition, reformers succeeded in pushing forward a new candidate-centric, primary system that weakened political parties. The primary system – unique to America – has had a lasting impact on our democracy and continues to shape reform today.

One area of reform from the Progressive Movement has received little attention. It relates to electoral systems. Political thinkers at the time took note of the link between political dysfunction and the system of voting. Two national organizations sprung up to advance electoral reform. One of these organizations produced a set of model laws that could be adopted at the local level. The model laws advocated preferential voting systems, including the Alternative Vote and the Single Transferable Vote described earlier. A number of cities adopted these systems. However, the legacy of this reform effort is checkered. By focusing on local government, the reforms did not affect partisan elections at the state and federal level. Ultimately, the model failed to gain momentum and was abandoned by every jurisdiction except Cambridge, Massachusetts. Further, it took the focus off single member, winner-take-all voting as the source of polarization and dysfunction in government. Instead, it placed blame on political parties. Substituting parties for winner-take-all elections as the cause of dysfunction has hampered reform efforts to this day.

The Road Not Taken

The Progressive Era saw an explosion of activity by reformers searching for ways to cure the ills that afflicted American society. In addition to expanding democracy, activists focused on the dysfunction of the political system. To that end, a group met at the Chicago World Fair in 1893. Also known as the Columbian Exposition, this event marked the 400th anniversary of Christopher Columbus’s cross Atlantic voyage. Through its vision of an energetic, urbanized nation, the Exposition proved to be a cultural watershed. Designers know it for the Beaux Arts “White City’” and the beginning of the City Beautiful movement. Many other firsts happened there, including Frederick Jackson Turner’s lecture on the Closing of the American Frontier, the creation of the Ferris Wheel, first recitation of the Pledge of Allegiance and the introduction of Cream of Wheat and Pabst Blue Ribbon beer. Erik Larson’s The Devil in the White City offers one of the best dramatic accounts of Daniel Burnham’s remarkable feat in producing this event.

The Progressive Era saw an explosion of activity by reformers searching for ways to cure the ills that afflicted American society. In addition to expanding democracy, activists focused on the dysfunction of the political system. To that end, a group met at the Chicago World Fair in 1893. Also known as the Columbian Exposition, this event marked the 400th anniversary of Christopher Columbus’s cross Atlantic voyage. Through its vision of an energetic, urbanized nation, the Exposition proved to be a cultural watershed. Designers know it for the Beaux Arts “White City’” and the beginning of the City Beautiful movement. Many other firsts happened there, including Frederick Jackson Turner’s lecture on the Closing of the American Frontier, the creation of the Ferris Wheel, first recitation of the Pledge of Allegiance and the introduction of Cream of Wheat and Pabst Blue Ribbon beer. Erik Larson’s The Devil in the White City offers one of the best dramatic accounts of Daniel Burnham’s remarkable feat in producing this event.

One organization lost in the ether of history also got its start at the Columbian Exposition: the Proportional Representation League. During the Exposition, this group organized its first meeting at the Memorial Art Institute. It aimed to promote the concept of proportional voting. Several prominent members included Rhode Island Governor Lucius Garvin, federal judge Albert Maris, and economist and labor reformer, John Commons. Commons provided the intellectual heft for this organization. After studying at Oberlin College and Johns Hopkins, Commons went on to teach at the University of Wisconsin for nearly 30 years. He pioneered research on the relationships among labor, market structure, collective action and social change. He has been credited for “the Wisconsin Idea,” a pipeline of ideas from the university to the legislature during the Progressive Movement. While at the university, Commons authored bills on workers compensation, unemployment insurance and the regulation of utilities. The Wisconsin Idea and its agenda helped make Bob LaFollette a national figure.

One organization lost in the ether of history also got its start at the Columbian Exposition: the Proportional Representation League. During the Exposition, this group organized its first meeting at the Memorial Art Institute. It aimed to promote the concept of proportional voting. Several prominent members included Rhode Island Governor Lucius Garvin, federal judge Albert Maris, and economist and labor reformer, John Commons. Commons provided the intellectual heft for this organization. After studying at Oberlin College and Johns Hopkins, Commons went on to teach at the University of Wisconsin for nearly 30 years. He pioneered research on the relationships among labor, market structure, collective action and social change. He has been credited for “the Wisconsin Idea,” a pipeline of ideas from the university to the legislature during the Progressive Movement. While at the university, Commons authored bills on workers compensation, unemployment insurance and the regulation of utilities. The Wisconsin Idea and its agenda helped make Bob LaFollette a national figure.

The meeting in Chicago occurred well before Commons’ tenure in Wisconsin. He was only 30 years old and just starting his academic career. Nevertheless, he managed to give a keynote speech to the Proportional Representation League in Chicago. He advocated the Swiss voting system based on list proportional representation (List PR). He continued to develop his ideas on electoral systems in his book Proportional Representation published three years later. In it, Commons surveys the range of reform efforts percolating at that time and demonstrates a keen technical understanding of electoral systems. He examines how different systems influence the behavior of voters. He sees clearly that majority voting systems fail the test of fairness and equality because they exclude minor parties and independent movements from government. He cites a number of jurisdictions, including the Illinois state legislature, experimenting with cumulative voting – where voters get as many votes as the number of seats and can “plump” their vote on one candidate to boost that candidate’s chances. Commons concludes that the cumulative vote results in guesswork and wasted votes since a voter can assign multiple votes to one candidate or spread the votes across several preferred candidates. Commons intuitively understands the complexity such a choice presents to voters. Instead of drawing a direct connection between a voter’s preference and an electoral outcome, the cumulative vote imposes strategic considerations about how the allocation of votes may impact multiple candidates.

He then turns to the Single Transferable Vote. As discussed previously, Thomas Hare created this system in response to the suppression of minority viewpoints by the winner-take-all system. Commons writes that the Single Transferable Vote was described as the “classical form of proportional representation from the great ability with which it was presented by its author, Mr. Thomas Hare, and advocated by John Stuart Mill.” Beyond some practical challenges with the system, Commons cuts to the chase: “The Hare system is advocated by those who, in a too doctrinaire fashion, wish to abolish political parties.”

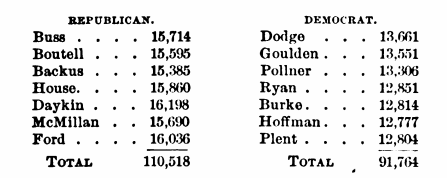

Commons asserts that voters primarily vote for individuals based on membership in a party. The characteristics of an individual candidate are secondary to party affiliation. Commons points to the outcome of “general ticket” voting in the U.S. as evidence for his thesis. The general ticket allows voters to vote for a candidate for each of several “at large” seats; however, each candidate requires a majority to win. Despite having the freedom to vote for a candidate from any party for each seat, voters invariably choose candidates from the same party. Consequently, all of the candidates from one party tend to win or lose the election by the same margin.

Commons asserts that voters primarily vote for individuals based on membership in a party. The characteristics of an individual candidate are secondary to party affiliation. Commons points to the outcome of “general ticket” voting in the U.S. as evidence for his thesis. The general ticket allows voters to vote for a candidate for each of several “at large” seats; however, each candidate requires a majority to win. Despite having the freedom to vote for a candidate from any party for each seat, voters invariably choose candidates from the same party. Consequently, all of the candidates from one party tend to win or lose the election by the same margin.

Commons relays the story of Thomas Gilpin, an American who devised a proportional system more than a decade before Hare. Like Hare, Gilpin was driven by a desire to give minority groups a voice in government. He presented the idea of proportional voting at a meeting of the Philosophical Society of Philadelphia in 1844. Moreover, he worked out the mechanics of establishing the quota for multi-member districts well before Hare did. But instead of having voters rank candidates as with Hare’s preferential voting system, each voter casts only one vote for a party. Commons argues that the “presentation” of this system – a choice among parties – comports with how voters want to express their preference. According to Commons, the psychology of voters should figure importantly in how to structure the voting system, and a party-based proportional system closely aligns with that psychology.

Commons shows how proportional voting evolved in Europe and then describes the system in Geneva, Switzerland as a worthy model. It allows voters to use cumulative votes for individual candidates but uses the total number of votes cast for a party to determine each party’s share of representation. In this manner, the system has a mechanism – like Mixed Member Proportional or Open List PR – to ensure parties end up with the number of seats proportional to the total votes they receive. At the same time, it allows voters to supersede any ranking of candidates by a party. By highlighting the logic of electoral systems that elevate parties above candidates in voting decisions, Commons foreshadows why List PR systems emerged as the dominant electoral system in the 20th century. His work also underscores the momentum proportional voting had at this time, describing various legislation, including a recent bill introduced in Congress for such a list proportional system.

In sum, there was considerable support for proportional voting at the end of the 19th century. Gilpin proved that the U.S. could be an innovator in electoral design. John Calhoun provided the theoretical basis for minority representation that inspired Hare. Commons and other thought leaders picked up that mantle as interest in reform increased during the second half of the 19th century. They understood and articulated the logic of party-centered proportional representation. Commons could see that parties are a creature of the voting system in which they operate and not vice versa. In a winner-take-all system, “the party becomes a machine, sustained by spoils and plunder, and there is no freedom for the voter.” In contrast,

Proportional representation … is based on a frank recognition of parties as indispensable in free government. This very recognition, instead of making partisan government all-powerful, is the necessary condition for subordinating parties to the public good. To control social forces, as well as physical forces, we must acknowledge their existence and strength, must understand them, and then must shape our machinery in accordance with their laws. We conquer nature by obeying her.

Open list PR accomplishes this by allowing voters to “control the nominations of their party” and giving voters the “power to defeat obnoxious candidates without endangering the success of the party” – not by eliminating parties from the decision-making process of voters. With the creation of the Proportional Representation League in Chicago, the U.S. was poised to address the problems created by winner-take-all systems. But that did not come to pass.

The National Civic League

Five months after John Commons gave his address at the Columbian Exposition in Chicago, another group met in Philadelphia at the National Conference for Good City Government. It boasted an all-star cast, including future president, Teddy Roosevelt, future Supreme Court Justice, Louis Brandeis, and iconic landscape architect and social critic, Frederick Law Olmsted. They met to discuss the “incompetence, inefficiency, patronage and corruption in local governments.” A new organization called the National Municipal League sprung into existence at this convention. It continues to this day as the National Civic League, providing guidance and support on best practices for local governments around the country.

The League championed significant reforms that included nonpartisan elections, a city manager form of government and inclusive civic engagement. Significantly, the League created the Model City Charter, a crucial tool encouraging best practices. Still in use today, the Charter serves as a “blueprint” for local government charters, which are akin to the constitution or legal framework that governs a city. The Model City Charter is now in its eighth edition. As an example, it recommends that a professional manager run city government while an elected, nonpartisan council act as a board setting the policy direction for the city and overseeing the manager. The model charter sets forth detailed provisions for the administration of budgets, duties of city officials and staff and the conduct of local elections. Most recently, it outlines steps to improve inclusiveness and prohibit discrimination.

Preferential Ballot

One of the few failed efforts undertaken by the Model City Charter relates to electoral reform. In 1914 at a meeting in Baltimore, the League presented “Municipal Home Rule and a Model City Charter.” This document covered a number of issues that would shape local government in the years to come, including initiatives, nominations and elections, referenda and city management. Two ideas contained in this model charter – the “Preferential Ballot” and “Proportional Representation” – continue to influence ideas within the electoral reform community – despite their failure to take hold during the 20th century.

Under the section of the Model Charter entitled, “Preferential Ballot,” it states “All ballots used in the election held under the authority of this charter shall be printed by the city and shall contain the names of the candidates without party or other designation.” The nonpartisan aspect of this section is consistent with other sections of the charter related to local elections and in keeping with the anti-party ethos of the Progressive Movement. The model provides that each ballot shall have columns with the names of candidates so that voters can mark their first choice, second choice and “other choices.” It says “If any candidates receive a number of first choices equal to a majority of all the ballots cast, they shall be declared elected in order of the votes received. If no candidate receives a majority, election officials then go on to count the second choice.” As discussed in the essay on majority voting systems, this proposal matches the Alternative Vote used sparingly in other countries. Currently, its use is limited to Fiji, Papua New Guinea and the lower chamber in Australia.

Note 12 on Proportional Voting

The Model Charter contains two important notes. Note 7 says, “For all cities desiring proportional representation the provisions therefor [are] set forth in Appendix B.” Note 12 provides more detail on proportional voting. It reiterates the desirability of an at-large system where candidates run city-wide in order “to eliminate the evils of ward representation.” However, it acknowledges that at-large districts in a winner-take-all system has “this disadvantage that they do not ensure minority representation and that the watchful care exercised over a city government by those who are in opposition may be entirely absent. In order to remedy this defect, a system of proportional representation may be introduced.” These comments acknowledge that winner-take-all systems deny minority representation and that proportional voting offers a remedy.

Note 12 explains the “two well-proved methods by which the system of proportional representation can be applied. One is the List system, in use in Belgium, Sweden, Switzerland and elsewhere; the other, the Hare system, in use in Tasmania and South Africa and incorporated for Irish parliamentary elections in the Parliament of Ireland Act recently passed.” Further, the Town of Ashtabula, Ohio had just adopted the Hare system. Of the two systems, the Hare System “gives the voter more perfect freedom in the expression of his will than does the List” by allowing voters to mark individual names rather than party. As importantly, the system designers at the time believed the Hare system “more effectively discourages the retention of national party lines in city government.” Consequently, the Model Charter selected the Hare system for those cities opting for a proportional system.

As discussed previously, leading reformers of the Progressive Movement blamed political parties for the pervasive and rampant corruption in government. Therefore, reforms centered on weakening the authority of parties. This anti-party sentiment tipped the balance in favor of Single Transferable Vote or “Hare System” over list PR as proposed by John Commons. The Hare system presented individual names on the ballot rather than party names consistent with the Charter’s advocacy of nonpartisan elections (i.e., elections in which party labels do not appear on the ballot). Further, it prevented national parties from controlling nominees, making it easier for reformers to attack the patronage system plaguing American politics at this time.

Electoral Reform at the Local Level

With the introduction of preferential voting in the 1914 Model Charter, the U.S. set off on a course that hindered the long-term prospects for significant electoral reform. It is important to note the major parties had little incentive to promote reform. In contrast to other industrialized nations at this time, neither of the two major parties perceived a significant threat of replacement by a worker’s party. That is not to say the U.S. lacked a labor movement. In some respects, the U.S. experienced more labor unrest and violence than other economically advanced nations. Jonathon Rodden shows in Why Cities Lose that worker parties in the U.S. enjoyed similar levels of support in dense urban districts as these parties did in other nations. Despite pockets of strong support, worker parties failed to win many seats held by the Democratic or Republican Parties. There are numerous theories why a labor party in the U.S. failed to match its strength in other industrialized countries. Certainly, a vast new nation with abundant opportunities presented a starkly different landscape compared to Europe’s feudal history and concentrated urban areas. Regardless, the lack of threat from a worker party at the height of the labor movement meant that neither major party saw any reason to advocate for proportional voting as a means of self-preservation.

Consequently, the push for electoral reform in America came at the local level as part of the good government movement. Given the mission of the National Municipal League, the Model Charter only addressed local elections, and as stated, the League advocated for nonpartisan elections. While the desire to crush local party machines may have driven the League to support nonpartisan elections, such elections succeeded for other reasons. Local politics does not depend on national party distinctions. Policy agendas typically focus on clean water, policing, housing, transportation and sanitation. Recall Madison’s insight in Federalist 10 – the perspective of political leaders correlates to the number of their electors. A small electorate focuses officials on the “lesser interests” of a locality while a large electorate urges officials to “pursue great and national objects.” Local government falls in the first camp. As such, cities do not require big philosophical debates that benefit from a party system to frame policy distinctions. Cities require leaders who can work together on a common agenda, building needed infrastructure and managing budgets.

The political support for the Municipal League and the inclusion of electoral reform on its agenda stole the energy from the Proportional Representation League – despite its intellectual heft and laser focus on electoral reform. Lacking funds to advance its reform agenda more broadly, the Proportional Representation League was eventually collapsed into the Municipal League. Consequently, the energy for electoral reform in Congress and the states dissipated. The model charter became the de facto source of electoral reform in the U.S. In the decades following publication of the 1914 model, a number of cities adopted preferential voting systems. After Ashtabula in 1915, Boulder, Kalamazoo, Sacramento and West Hartford followed suit. By the mid-1920s, several large cities such as Cincinnati, Toledo and Cleveland adopted the model charter. New York City adopted it in 1936, which spurred other cities to join the trend. In all, nearly two dozen cities joined the reform movement.

Douglas Amy, a proponent of proportional voting and professor at Mt. Holyoke College, describes this period in “A Brief History of Proportional Voting in the United States.” He notes a study that examined the impacts of proportional voting on the cities that adopted it. The authors of that study draw several conclusions. First, parties won seats more proportionally to votes received. Second, racial and ethnic minority groups gained seats in city government. Finally, researchers found some support that preferential ballots helped break the power of political machines by allowing voters to choose representatives rather than the parties.

Nevertheless, adoption of the model charter had limited effects. It did not result in the emergence of vibrant multi-party governments across the U.S. More importantly, it did not gain a lasting support base among the populace. Amy attributes the abandonment of the Single Transferable Vote by cities to a range of factors. They include the rejection of other elements of the model charter such as the city manager form of government, legal challenges by major parties, and backlash against minority representatives, particularly in the days before the Civil Right movement. Powerful interests also financed referenda to repeal proportional representation. As of today, Cambridge remains the last holdout deploying the original model charter from 1914. No other city uses the Single Transferable Vote.

Lessons from the Model Charter

There are important lessons in the history of reform efforts at the local level. Most importantly, proportional systems work best with political parties on the ballot. Proportional representation arose out of a desire to afford minority groups – aligned along broad public interests – a voice in government. Parties provide a necessary vehicle to allow groups to advance their political agenda. In contrast, local government tends to function well without partisan elections. As mentioned, the National Municipal League introduced model charter language supporting nonpartisan elections in the early 20th century and has stuck with that position. Most cities in the U.S. have adopted this language and continue to hold nonpartisan elections. Local governments can satisfy the needs and desires of the electorate without party representation for the reasons identified by Madison and other political thinkers: representatives of small geographic areas attend to constituents’ immediate practical needs. Voters do not need parties to signal which officials are better adept at meeting these needs.

The other lessons relate to preferential voting systems. As we saw in the essays on majority and proportional voting, preferential voting has a spotty record. Very few countries use them. The Republic of Ireland has used the Single Transferable vote for nearly 100 years and has withstood referenda to eliminate it. Obviously, there is an attachment to it by the public. However, the only other nation using the Single Transferable Vote for elections to its lower legislative chamber is Malta. And similar to the experience with cities in the U.S., countries such as Estonia and South Africa abandoned the system after adopting it. Single Transferable Vote simply does not breed strong loyalty among voters. It requires voters not only to consider their preference for a candidate, they must also weigh the impact of the ranking system on other candidates. Is it better to vote for only one candidate? Will voters hurt a preferred choice if they rank a rival highly? These questions add complexity to a process seeking to unlock the collective mind of the electorate so that government can carry out the will of the people.

Ranked Choice Voting

Frustration over gerrymandering, unfair representation, limited choice and polarization has rekindled reform efforts in recent years. The current movement has two strains – one originating in Ohio and the other on the West Coast. Ohio was ground zero for the reforms in the 20th century. Many of its major cities adopted the Single Transferable Vote suggested in note 12 of the 1914 model charter. These cities withstood multiple efforts at repeal. Cincinnati was the last city in Ohio to succumb to these repeal initiatives. With it, Black representation on city council ended. Other ethnic groups lost representation. However, the experience in Ohio was not forgotten. A nonpartisan organization called FairVote formed in Cincinnati in 1992 to kick start the reform movement.

FairVote advocates the same preferential voting systems contained in the National Municipal League’s 1914 Charter. Instead of referring to them as the Alternative Vote and the Single Transferable Vote, FairVote uses the terms Ranked Choice Voting (RCV) and Proportional Ranked Choice Voting (PRCV), respectively. At the federal level, FairVote supports the Fair Representation Act. The Act would require PRCV for Congressional races. Any states with five or fewer seats would have one multi-member district. States with six or more seats would have more than one multi-member district with no less than three seats. The Act also requires an independent redistricting commission when a state has sufficient congressional seats to require more than one multi-member district. Any state with one or more multi-member districts would rely on PRCV. The Act was introduced in Congress in 2017 and 2019. Among the Act’s seven sponsors, Rep. Don Beyer of Virginia has been its most vocal advocate.

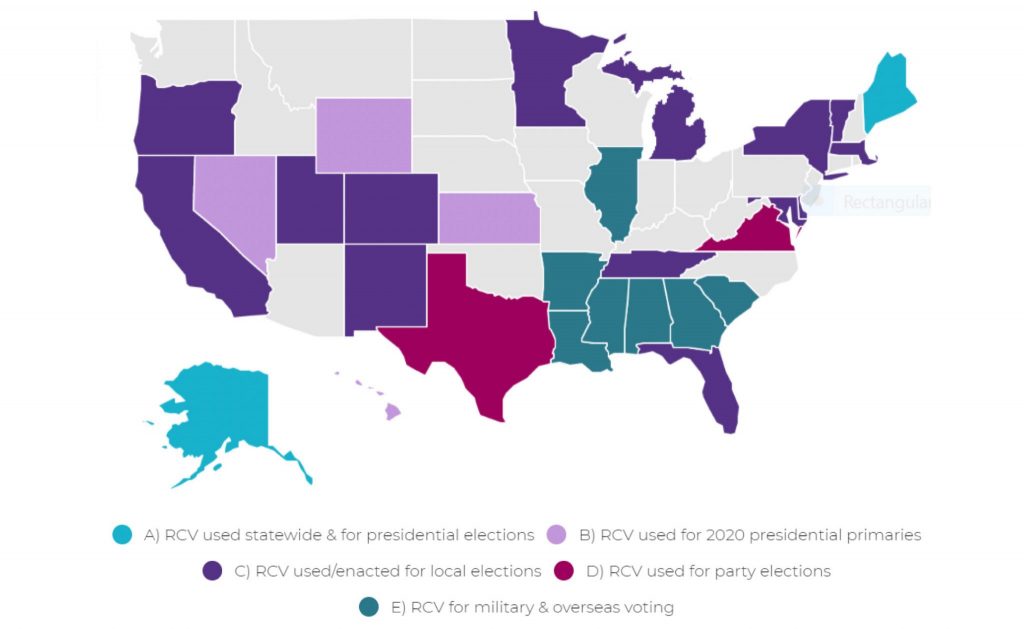

Apart from introduction of the Fair Representation Act in Congress, most of the reform activity centers on the winner-take-all, RCV system. FairVote tracks implementation of RCV in jurisdictions across the U.S. As reflected in the map below, its most common use occurs in party primaries and local elections where the election focuses on individual candidates rather than choices among parties. Also known as “instant run-off voting,” RCV is an effective tool when it is difficult to hold in-person elections or run-off elections such as the oversees military. New York City recently used RCV in the 2021 mayoral election. A number of cities in the State of Utah will use RCV in 2021.

The most significant victory to date for RCV occurred in Maine in 2016 when the Ranked Choice Voting Act passed by referendum with 52% of the vote. The law went into effect in 2018 and applies RCV to all primary and general elections for governor, state legislature, Congress and President. In 2019, legislation passed to expand RCV to the presidential primary and general election in Maine. Given the recent use of RCV in Maine, analysis on its effects remains limited.

Blanket Primary

The other strain of electoral reform relates to primaries. It builds on the primary system unique to the U.S. and is based on a view that diminishing the role of parties serves the cause of reform. As noted earlier, the Progressive Movement led to the creation of closed and open primaries in different states. The former requires a voter to be affiliated with a party to vote on that party’s ballot in a primary election. The latter allows a voter to access a party’s ballot in a primary election regardless of the voter’s party affiliation. California continued to push the envelope toward removing party control over primary elections with Proposition 198, which passed in 1996. This measure is known as a blanket primary. With a blanket primary, voters receive a single ballot listing candidates from all parties for the primary election. Voters can choose candidates as they wish. For instance, they can vote for a Democrat for the Democratic Party’s U.S. Senate candidate and a Republican for the Republican Party’s Gubernatorial candidate.

The U.S. Supreme Court initially stuck down this law in California Democratic Party v. Jones (2000) as a violation of the First Amendment’s right to freedom of association. Justice Scalia wrote the 7-2 opinion, stating “Proposition 198 forces political parties to associate with – to have their nominees, and hence their positions, determined by – those who, at best, have refused to affiliate with the party, and, at worst, have expressly affiliated with a rival… A single election in which the party nominee is selected by nonparty members could be enough to destroy the party.” To overcome the constitutional objection, reformers on the West Coast created the nonpartisan blanket primary. This type of primary places all candidates for an office on the same ballot without listing party affiliation. Because these primaries are nonpartisan, the courts have ruled them constitutional. Justice John Roberts concurred in a 2008 decision, stating as long as no reasonable voter would believe the candidates on the ballot are nominees of or otherwise associated with a party, the system would likely be constitutional.

Once the U.S. Supreme Court opened the door, reformers on the West Coast began introducing bills to establish blanket primaries. In California and Washington, the top two vote-getters for each office now go on to the general election regardless of party label. That means two candidates of the same party may face each other in the general election. In 2020, voters in Alaska approved Measure 2, which combines a top four blanket primary system and a RCV system for the general election. Except for the presidential election, all federal and state offices will be determined under this system. With a top four system, any combination of parties may be on the ticket in the general election.

Katherine Gehl, a business owner, and Michael Porter at Harvard Business School support the Alaska measure as well as Unite America, a nonpartisan advocacy organization. In The Politics Industry: How Political Innovation Can Break Partisan Gridlock and Save Our Democracy, Gehl and Porter apply the principles of economic competition to understand how American democracy has devolved into a corrosive “duopoly.” They connect polarization and non-competitive general elections to party control over primaries, which makes it difficult for moderate candidates to succeed. They believe elections will produce more competition and more “moderate, compromise-oriented politicians” when candidates must appeal to voters from both major parties. Instead of the most extreme elements of each party selecting candidates in the primary, a larger, moderate group of voters will have more power according to the authors.

Measure 2 goes into effect in 2022 so its effects remain to be seen. Studies focusing on the results of California’s top two system have shown parties with multiple candidates on the primary ballot have been hurt from vote splitting. Thus far, there is no evidence of greater success for moderate candidates, and turnout among unaffiliated voters has not increased. More importantly, this strain of reform misses the source of the problem. As shown by Duverger’s Law, polarization and extreme candidates result from majority voting in single member districts. Blanket primaries keep intact majority voting in single member districts. Equally important, this reform continues the misplaced effort to weaken political parties begun during the Progressive Movement. As discussed, political parties are critically important in organizing groups around issues important to voters, solving the calculus of voting, driving legislation through a political caucus and holding candidates accountable once they are elected.

Conclusion

An examination of electoral reform in the U.S. reveals a road littered with missed opportunities. America produced some of the great thinkers on electoral reform. The work on proportional voting by Thomas Gilpin predated Thomas Hare, who in turn was influenced by John Calhoun. American innovators understood the winner-take-all voting system stifled minority voices, led to unfair outcomes and stirred divisiveness. Consequently, numerous states and local governments experimented with forms of proportional voting in the second half of the 19th century. John Commons studied these efforts and proposed a proportional system that recognized the way voters make decisions, placing a party framework above individual candidate selection. His words inspired a new organization, the Proportional Representation League, that came to life just at a moment when the U.S. embraced serious reform.

Unfortunately, America missed that opportunity. Instead, it ambled down a different path. Leading reformers diverted electoral reform from state and federal elections to the local level at a time when cities adopted nonpartisan elections. Moreover, the model charter for reform employed a candidate-centric, preferential voting system rarely used by other countries. A number of cities adopted it from the 1920s to the 1950s, but each one eventually abandoned it with the exception of Cambridge. Historians cite different reasons for this outcome, but what is clear, the voters gave in to forces seeking to eliminate preferential voting. That is not the case in countries using list proportional voting, the predominant system in the world. Now that political and economic circumstances rival those of the Progressive Movement, reformers have taken up the torch for preferential voting systems and other candidate-centric measures. American’s rich history of innovation based on a recognition that winner-take-all, single member districts can destroy democracy largely has been lost. Can we reclaim our role as innovator?

Mack Paul is a member of the state advisory board of Common Cause NC and a founding partner of Morningstar Law Group.

Parts in this series:

Introduction: Building Democracy 2.0

Part 1: What Is Democracy and Why Is It Important?

Part 2: How the Idea of Freedom Makes the First Innovation Possible

Part 3: The Second Innovation that Gave Rise to Modern Democracy

Part 4: The Rise and Function of Political Parties – Setting the Record Straight

Part 5: How Political Parties Turned Conflict into a Productive Force

Part 6: Parties and the Challenge of Voter Engagement

Part 7: The Progressive Movement and the Decline of Parties in America

Part 8: Rousseau and ‘the Will of the People’

Part 9: The Dark Secret of Majority Voting

Part 10: The Promise of Proportional Voting

Part 11: Majorities, Minorities and Innovation in Electoral Design

Part 12: The Misdirected Attempts at Electoral Reform in the U.S.

Part 13: Building Democracy 2.0: The Uses and Abuses of Redistricting in American Democracy