Report

Report

Charge Report: Community Redistricting Report Card

Related Issues

About CHARGE

CHARGE, the Coalition Hub for Advancing Redistricting & Grassroots Engagement, is a space for groups that organize people in the states and in local communities. CHARGE is composed of organizations that have presence in different states and that deploy different organizing strategies while uniting around the common goal that redistricting must be transformed to allow more voices to participate, be heard, and be represented.

This coalition held 30 joint trainings, reaching over 2,200 activists and community leaders in all 50 states through our Redistricting Community College. Individual CHARGE organizations conducted many more spinoff trainings. In addition to introducing participants to redistricting, our trainings provided the know-how, strategies, and tools organizations need to be effective advocates. The trainings introduced participants to the redistricting process in each state, the Voting Rights Act, how to talk about communities, how to work in coalitions, and how to utilize free online mapping resources.

The Community Redistricting Report Card Structure

The Community Redistricting Report Card reflects on this redistricting cycle, rating each state’s redistricting process based on community feedback. This report is the product of hundreds of on-the- ground interviews and surveys conducted by CHARGE. By engaging with organizations, advocates, and organizers from communities in every state, this report represents a holistic view of the redistricting experience—what worked, what did not work, and what can be done differently in the future.

Each interview and survey asked questions surrounding each state’s redistricting process, including the transparency and accessibility of the process, the role of community groups, the organizing landscape, and the use of communities of interest criteria.

This report contains a background on each state’s redistricting scheme, the successes and challenges, and lessons learned to improve future redistricting cycles. The letter grade given to each state reflects the aggregate feedback and grades given by our interviewees—how they viewed their state’s redistricting process.

Redistricting Challenges and Report Findings

Under the best of circumstances, public participation in redistricting can be challenging. In states where legislators draw districts, they jealously guard their power so they can draw districts behind closed doors to maximize partisan advantage and protect themselves from potential challengers. This cycle, legislators often achieved that goal by limiting the number of public redistricting hearings, scheduling them when many potential participants were working, providing limited translation services or disability access, and simply drawing district maps in secret without regard to public input.

In addition to those challenges, which are common to every redistricting cycle, participants in the 2020 cycle faced unprecedented barriers to public participation. States received census data six months later than usual due to a pandemic-driven change to the U.S. Census Bureau’s counting schedule. This condensed the time available to organize communities and provide meaningful feedback in response to draft maps. The pandemic also made it difficult at certain critical points in the redistricting cycle to host in-person organizing sessions that are crucial to building power.

Despite these numerous barriers to participation, organizers found creative ways to conduct public education and engage communities. With the support of CHARGE resources, democracy advocates across the country trained their fellow citizens on the connection between redistricting and effective democratic representation, mapping their communities to give those drawing final maps specific and usable feedback, and giving clear, concise, and compelling testimony at redistricting hearings.

Although efforts to organize communities varied greatly due to local circumstances, some common themes are discernable.

Key Findings

- Independent citizen redistricting commissions are significantly more likely to seek public feedback and integrate it into voting maps. The screening process for independent commissions eliminates individuals with a personal bias in the drawing of districts. As a result, these commissions tend to attract individuals making a good faith effort to learn about communities and make informed decisions about how to ensure the fairest representation possible for the highest number of people.

- Not all redistricting commissions are created equal. Some state redistricting commissions include elected officials, allow elected officials to have a greater say in the appointment of redistricting commissioners, or give legislators a final say in the approval of maps. These commissions are far more likely to suffer from partisan deadlock or produce maps that ignore public input and instead focus on partisan, racial, or incumbent advantage.

- Legislators often seek to make the process of drawing districts as secretive as possible. Advocates had to engage in intensive organizing to ensure the public would have a meaningful role in redistricting and that hearings would be accessible to the public. This often meant fighting for proper notice of hearings, transparent proceedings, translation services, and online testimony options. Moreover, when opportunities for input did exist, they did not always translate into wins for communities or real changes to maps. This was sometimes used against communities when redistricting bodies claimed their process was “the most transparent ever” and provided many opportunities for public input only to ignore the vast majority of input given. Transparency and input are needed and sorely lacking, but it cannot be the only marker for an equitable redistricting process.

- Effective organizing can result in wins for communities even in states with a partisan and politician-led process, especially at the local level. Although politician-led redistricting processes tend to focus almost exclusively on incumbent protection and partisan or racial advantage, that does not mean all hope is lost. Advocates successfully pushed back on egregious community splits in several states when demonstrating the legal jeopardy such splits placed maps in, harmful impacts on those communities, and reasonable alternatives. In states with entrenched single party control and a politician-controlled process, local organizing resulted in key wins that made real differences in people’s lives.

- Communities of color are still being targeted and left out of the redistricting process. Population growth in most states was driven by communities of color, but that fact did not guarantee a seat at the table for those communities when redistricting decisions were made. Entrenched politicians who view these communities as a threat to their political power made the process inaccessible and then packed and cracked these communities into districts that limited their political power. Organizing communities of color to demand a voice in redistricting remains essential because they are often the targets of political disempowerment. Additionally, legislators are becoming more sophisticated in avoiding liability for Voting Rights Act violations. Activists should consider ways to collect evidence relevant to VRA cases when legislators attempt to cover their tracks.

- The least-change approach to redistricting limits the ability of communities of color to achieve effective representation in redistricting. In some states, legislatures and courts adhered to the idea that new districts should resemble old districts as closely as possible. The Supreme Court in Allen v. Milligan has rejected this fiction in states where communities of color have driven demographic changes. Least-change arguments have been used to make previous gerrymanders permanent, making it a harmful concept that dilutes the votes of communities of color and hinders fair representation.

Looking Forward

Some common themes regarding organizing successes and challenges also arose in our surveys and interviews that can help shape the future of redistricting work. These include:

- Linking redistricting to census messaging during “get out the count” efforts would have made subsequent public education easier. Outreach to historically undercounted communities prior to the census understandably focused on the importance of an accurate count to the allocation of government resources. However, some organizations expressed regret that they did not discuss the role an accurate count plays in ensuring effective representation in redistricting. They believe that driving home this point early and when they had increased resources for census count efforts would have made the task of inspiring the public to action on redistricting work easier.

- Earlier funding goes a long way, especially for community-based local organizations. In a charged political environment in which grassroots activists have many issues to choose from to invest their time and energy, public education that describes the central role redistricting plays in every substantive issue is crucial. This requires significant funding and staffing. Activists stated their hope that funding for public outreach, materials, training on mapping and giving testimony, and other tools might come earlier in future cycles and focus on local organizations to build greater momentum sooner. Local organizations are at the forefront of organizing around redistricting and often understand the political landscape better than national groups, but still can benefit from national support and training. Building civic engagement infrastructure throughout the 10-year cycle and far in advance of redistricting for work on related civil and voting rights issues is an important strategy for increasing capacity.

- Don’t let a community slip through the cracks just because it is not located in a swing state. Some organizations felt that it was more difficult to obtain funding and attention for redistricting work if they were not in a state that is competitive politically between the two major parties. However, as the full release of this report will make clear, effective representation can be obtained or denied to a community in any one of the 50 states regardless of its statewide competitiveness.We hope this report provides both information and inspiration. Community leaders stared down entrenched politicians and their powerful backers with energy and courage while demanding a seat at the table. Some succeeded. Some did not. But our collective efforts inspired thousands of people – neighbors, leaders, family and friends – to find their voice and make it heard in the halls of power, and to stay engaged.

This report is their story.

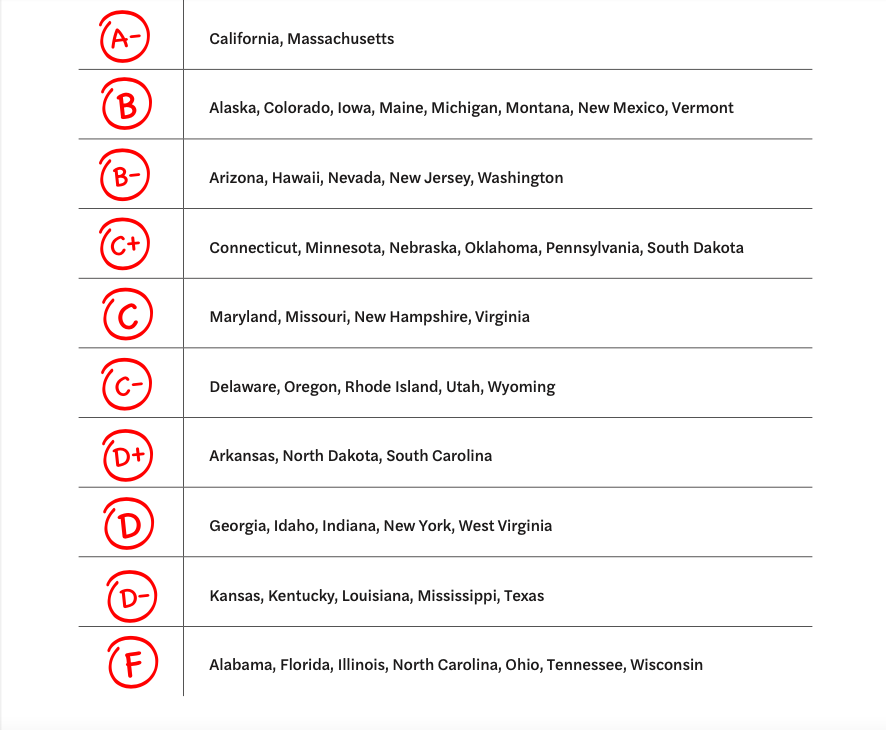

What Do These Grades Mean?

States received grades based on several factors related to the redistricting process and mapping outcomes. These include transparency, opportunities for public input, willingness of decision makers to draw districts based on that input, adhering to nonpartisanship, empowerment of communities of color, and policy choices such as rejecting prison gerrymandering.

Alaska

Arizona

Arkansas

California

Colorado

Connecticut

Delaware

Florida

Georgia

Hawaii

Idaho

Illinois

Iowa

Kansas

Kentucky

Louisiana

Maine

Maryland

Massachusetts

Michigan

Minnesota

Mississippi

Missouri

Montana

Acknowledgements

This report was co-authored by:

Sarah Andre, Redistricting Demography & Mapping Specialist, Common Cause, Kathay Feng, Vice President of Programs, Common Cause, Marijke Kylstra, Redistricting Coordinator, Fair Count, Elena Langworthy, Deputy Director of Policy, State Voices, Saundra Mitrovitch, Director, External Engagement, National Congress of American Indians, Dan Vicuña, Director of Redistricting and Representation, Common Cause, and Alton Wang, Equal Justice Works Fellow, Common Cause.

We thank Camille Hanson for research support, Kerstin Vogdes Diehn and Kristi Wood for design, Meghan Kearney for copyediting, Noam Kranin, Talha Muhammad, and Maurice Whitehurst for writing support, and the time of the hundreds of organizers who completed surveys and interviewed with us. We also thank Fair Representation in Redistricting for their generous financial support, without which this report nor the organizing work of CHARGE would have been possible.

Copyright © September 2023 CHARGE

Related Resources

Report

The Roadmap for Fair Maps in 2030

Report

Charge Report: Community Redistricting Report Card

Fact Sheet